Variable rates will likely be a benefit once again in the midterm

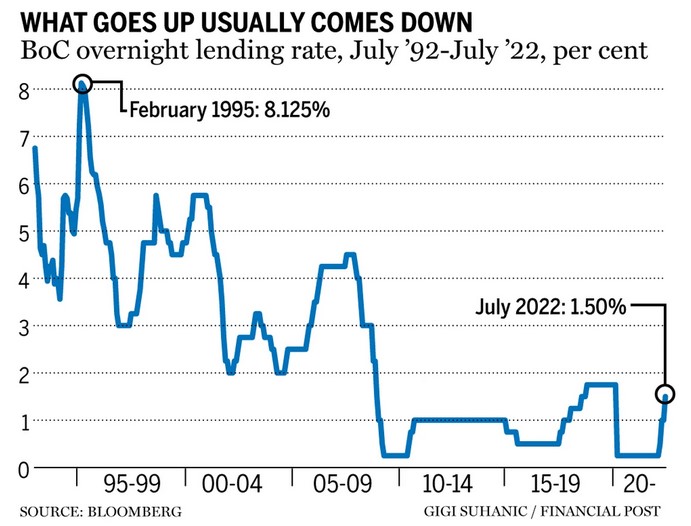

The Bank of Canada over the past 30 years has had six periods of interest-rate hikes, ranging from 1.25 to 3.2 percentage points, before this most recent set in 2022.

The one thing they all had in common was that it didn’t take long for each of them to be followed by a period of declining interest rates, ranging from 1.25 to 5.125 percentage points.

One logical reason for this is that rate rises are meant to slow down the economy, and rate declines are meant to boost the economy. There is a general view that the increases typically start too late, and so rates are still rising after the economy is already slowing. Once they really start to take effect, the impact can be too much, and the central bank has to do a quick about-face.

Let’s do a quick review of the six rises and falls since 1994.

In October 1994, the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate was 4.94 per cent. Over the next four months, it rose significantly to 8.125 per cent — a rise of 3.2 percentage points. Over the following nine months, it declined to 5.94 per cent, and one year later it was sitting at three per cent. This was a large rise and fall historically, but it outlines how quickly rates can rise and how steep the ultimate decline can be.

The next period of rate adjustments saw the overnight rate rise to 5.75 per cent from three per cent over a 15-month period in 1997 and 1998. The subsequent decline wasn’t as steep, but it did drop over the following nine months to 4.5 per cent in May 1999.

In October 1999, the rate was still 4.5 per cent, but then rose to 5.75 per cent by May 2000. One year later, it was back to 4.5 per cent and it was all the way down to two per cent by January 2002.

Over a 25-month period from March 2002 to April 2004, the rate went from two per cent to 3.25 per cent and back to two per cent.

During a relatively prosperous time, the rate rose to 4.5 per cent in July 2007 from 2.5 per cent in August 2005. But the financial crisis of 2008 started to rear its head, and rates fell first to three per cent by April 2008 and all the way to 0.25 per cent a year later.

More recently, the rate in June 2017 was at 0.5 per cent, rose to 1.75 per cent by October 2018, and then dropped to 0.25 per cent by March 2020 when COVID-19 began.

What does this mean for today? So far, we are 1.25 percentage points into an interest-rate-hiking cycle. Some think there are another one or two more points in front of us. Others think it will be less than that. What if the overnight rate goes from 0.25 per cent (where it was in February 2022) to 2.75 per cent? For many of us, that would be a bad thing because our borrowing costs would be meaningfully higher. However, if we were somewhat confident that rates would soon be heading down from there, would that ease our concerns?

History suggests this will happen. The six hiking cycles averaged 13 months in length. The current one is four months in. The six declining cycles began on average 5.7 months after the hikes stopped, but it happened within three months in three of the six scenarios. The average interest rate hike was 1.95 percentage points and the average decline was 2.85 percentage points.

History can be a guide, but certainly not a clear roadmap. If all we did was simply look at the averages here, it would suggest that we have another 0.7 percentage points of rate hikes, which would take another nine months to reach. Interest rates would then start to decline by September 2023 and eventually drop all the way back to 0.25 per cent (or more if it was possible).

Of course, each scenario is different, so things won’t simply follow these averages. The causes are different and the starting point on interest rates is different. That said, this cycle has been very repetitive over the past 30 years.

If I had to guess, I would expect the rate-hiking timeline will be shorter than 13 months, but that rates will move up by more than just 0.7 percentage points. I believe the start of the rate declines might happen sooner than September 2023. The implied policy curve for Canada currently suggests that rate hikes will peak in six months and then start to decline with the following year. This doesn’t mean that this is a fact, but it shows that even today, the implied policy rate is giving some indication of the same cycle we have seen several times before.

Another clue as to why the next cycle might look like the past is that even the Bank of Canada has said one of the reasons for increasing rates is so it will have some greater tools and leverage to help the economy by lowering rates if we go into a recession or something similar.

If that is the future, what does that mean for investors and borrowers?

Variable-rate borrowers will feel more pain in the near future, but it isn’t a one-way road. Variable rates will likely be a benefit once again in the midterm.

If you are looking at buying guaranteed investment certificates, annuities or bonds, it may still be a little early to lock in or invest, but there will likely be a sweet spot to do so later this year or in the first half of next year.

High inflation and higher interest rates seem like the obvious situation today, but this may shift in the not-too-distant future, so don’t go overboard with this investing thesis as it can turn on you. You want to be nimble.

The key message here is that we should not panic about runaway rate hikes. They will continue to rise, but it is also very likely that we will see rates fall shortly after the hikes stop. Maybe this rollover will happen by the end of this year or at some point in 2023, but being prepared for this scenario will allow for some investment opportunities and debt opportunities to be maximized.

Reproduced from Financial Post, July 12, 2022 .